Reflecting on the Laws of the Conservation of Energy and Ecosystems’ Exploitation

Matter/energy can be transformed from one form to another.Matter/energy can neither be created nor destroyed.When matter/energy is transformed from one form to another, there is a net loss.This loss is called entropy.A system that has been transformed and lost energy moves towards high entropy.A system that has its energies intact is a low entropy system.If a forest in a watershed is clear-cutAll the energies in the woodAre transformed and dispersed.The energy within topsoilThe energies embedded in the Earth dependent habitatsSupporting a multiplicity of livesAs a consequence of erosion is dispersed.The entropy of the watershed has been increasedBy the dispersal of these energiesThe energy so dispersed cannot be retrieved.

What then, watershed, what then.

A Manifesto for the 21st Century

We, of the Harrison Studio, believe

As do others, although differently

That a series of events have come into being

Beginning in the time of Gilgamesh and before

Beginning with agriculture and the first genetic manipulation

Beginning with culture of animals and ongoing genetic manipulation

Beginning with globalization six thousand years ago with the Salt Route

A little later, the Silk Route

And later and later…

Especially with science informed by Descartes’ clock

And with modernity recreating the cultural landscape

And deconstructing nature thereby

From the Industrial Revolution to the present

Until all at once a new force has become apparent

We reframe a legal meaning ecologically

And name it the Force Majeure

We, of the Harrison Studio assert As do others somewhat differently That the Force Majeure, framed ecologically Enacts in physical terms, outcomes on the ground Everything we have created in the global landscape Bringing together the conditions that have accelerated global warming Acting in concert With the massive industrial processes of extraction, production and consumption That have subtracted forests, and depleted top soil And profoundly reduced ocean productivity While creating a vast chemical outpouring into the atmosphere Onto the lands and within the waters That altogether comprise this Force Majeure

(for full text see Manifesto)

The Force Majeure Introduction

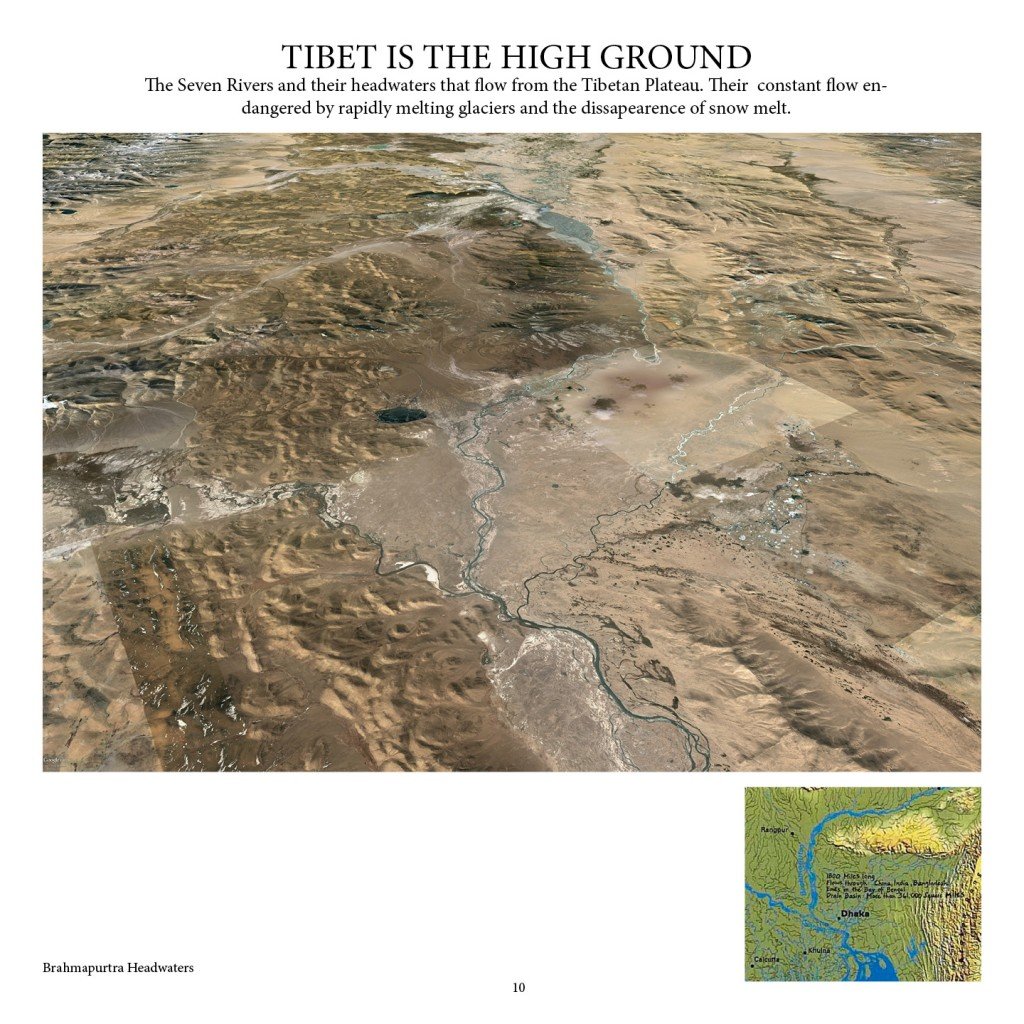

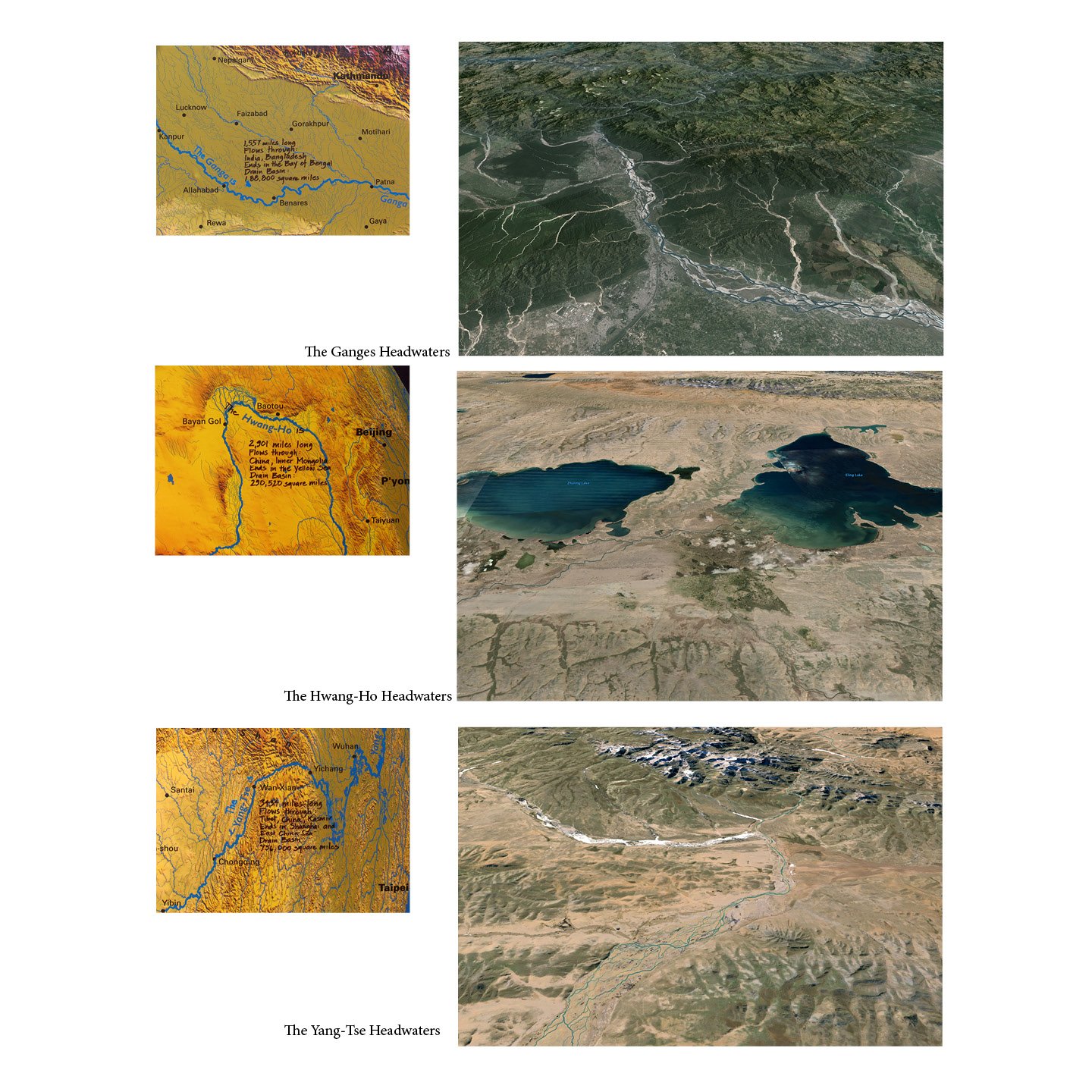

It was around 2007, early 2008. We had finished and repeatedly shown “Greenhouse Britain”, “Tibet is the High Ground” had its second iteration, as had “Peninsula Europe”. The first rewriting on “Peninsula Europe” had been on ocean rise and the second re-writing had been on the accompanying drought. I was suddenly reminded of walking in the woods with Richard Feynman in the Eucalyptus Grove at University of California San Diego. He was the science advisor to my artificial Aurora Borealis, just being completed at JPL for the American Pavilion at the ‘Expo 70’ in Osaka. Actually he had no interest in this work so he began talking about his equations. He said, “For a long time I have written these equations and always, something was missing.” Finally, he had an epiphany. He said, “That which was missing, was something. Therefore inferentially, nothing had been missing in the first place.” Exactly what that something was eluded me, but I found the persistence of the search and process of discovery electrifying. Moreover, the sum over its histories he used as a metaphor to approach a definition of the momentum of an electron, seemed an adventurous envisioning to me.

It happened that in writing this late phase to a life’s work we began to review almost 45 years of being and doing for something we called “salient” features. From our perspective, a salient feature is “something that appears again and again and in one form or another in any extended narrative.” Our body of work was no exception. For the purpose of simplicity we defined a salient feature as an invention subconsciously established by the psyche to guide or assist the processes of art-making. We discovered that something was missing in the majority of our work and that the salient feature in our work happened to be the absence of something. Obviously a very different something than Feynman was talking about.

The first indication of what would become an important salient feature was recognized during a morning conversation in 1970 after making a world map of endangered and extinct species for the “Fur and Feather” exhibition at the Crafts Museum in New York City. The research with a team of students had been exhausting. We asked ourselves a question, “What is the most Endangered Species on earth?” We concluded that the most endangered species wasn’t a species at all but a system. The Earth itself, or topsoil, was this endangered system. After all, anyone, anyone at all for any reason can interrupt or destroy or force the simplification of the ecosystem in the soil. It only takes a shovel. So our first clear eco-political work was “Making Earth” with a shovel, which itself was a metaphor for a bulldozer; the one of us making topsoil, the other planting in it. We did this before understanding collaboration was wanting to happen. This making and planting became, in a larger sense, a metaphor for the idea of regenerating the earth worldwide. Implicit was a second question. “Would it be enough, if all the topsoil was regenerated worldwide?” Clearly it wouldn’t be enough. Regenerating topsoil might simply be an invitation for further exploitation. Something was missing.

In 1973-1974, the work “San Diego is the Center of a World” was done. It made the argument that we were in an interglacial period and depending in some part on human behavior it would become warmer or colder sooner than later. Soon being a mere 500 years. But in either event, vast forces were at work and we had better begin planning about what to do. In retrospect this kind of planning or attitude toward planning was the first step in later works that pointed toward adaptation to systems change at great scale. The question “would it be enough” was slowly becoming a metaphor for systems wellbeing and “no” speculative planning by itself would not be enough. Something was missing.

In 1976 with an invitation from the French Scholar Michel Benemou, we went to the University of Milwaukee and his Institute of American Studies at the Northern edge of the Great Lakes. After some study he asked what we wished to do. We said, (to quote ourselves from an early chapter) “You know, some lunatics many years ago drew a line across the Great Lakes of North America, as if they could draw on the water. Then they gave half of the Great Lakes and the Great Lakes Watershed to Canada and they gave the other half to the country we are standing on.” So Michel asked again, “What do you have in mind?” We replied, “We wish to propose that the people of the Great Lakes Watershed of the United States and Canada withdraw from each of these two countries and collectively form a dictatorship of the Ecology.” We wrote and performed a rather long list of questions about how to form a dictatorship of the Ecology, always asking “But would it be enough” as a sort of refrain. But even then, neither one nor all that we proposed, would be enough. Something was missing.

In 1979 to 1980, at the end of the “Lagoon Cycle” in the “Seventh Lagoon”, we mapped the ocean rising as a consequence in good part of the human creation of fire. With global warming driving the rise of oceans, the two characters, the Lagoon Maker and the Witness pose the following questions “In this continuous beginning; this continuous re-beginning, will you feed me when my lands can no longer produce food?” “Will I house you when your lands are covered with water?” So far, some 35 years later, the answer in both cases appears to be “No” or “We don’t think so.” It seemed to us then and even more so now, that people helping people was a good thing to be doing, but by itself it would not be enough for whole systems well-being to continue. Something was seriously missing from our understanding of events and therefore absent from all the work we had done so far.

Ten years passed. In 1991 the Serpentine Lattice proposed that it would take commanding the 2,000 mile ridge line of the North American fog forest from San Francisco to Yakutat Bay Alaska in order to begin seriously encouraging the regeneration of what amounted to be about 50,000 square miles of clear-cut fog forest. We argued for an eco security system, not unlike the Social Security System, to fund this adventure. But again to the question “Would it be enough” the response, “No it would not be enough” had become almost a refrain.

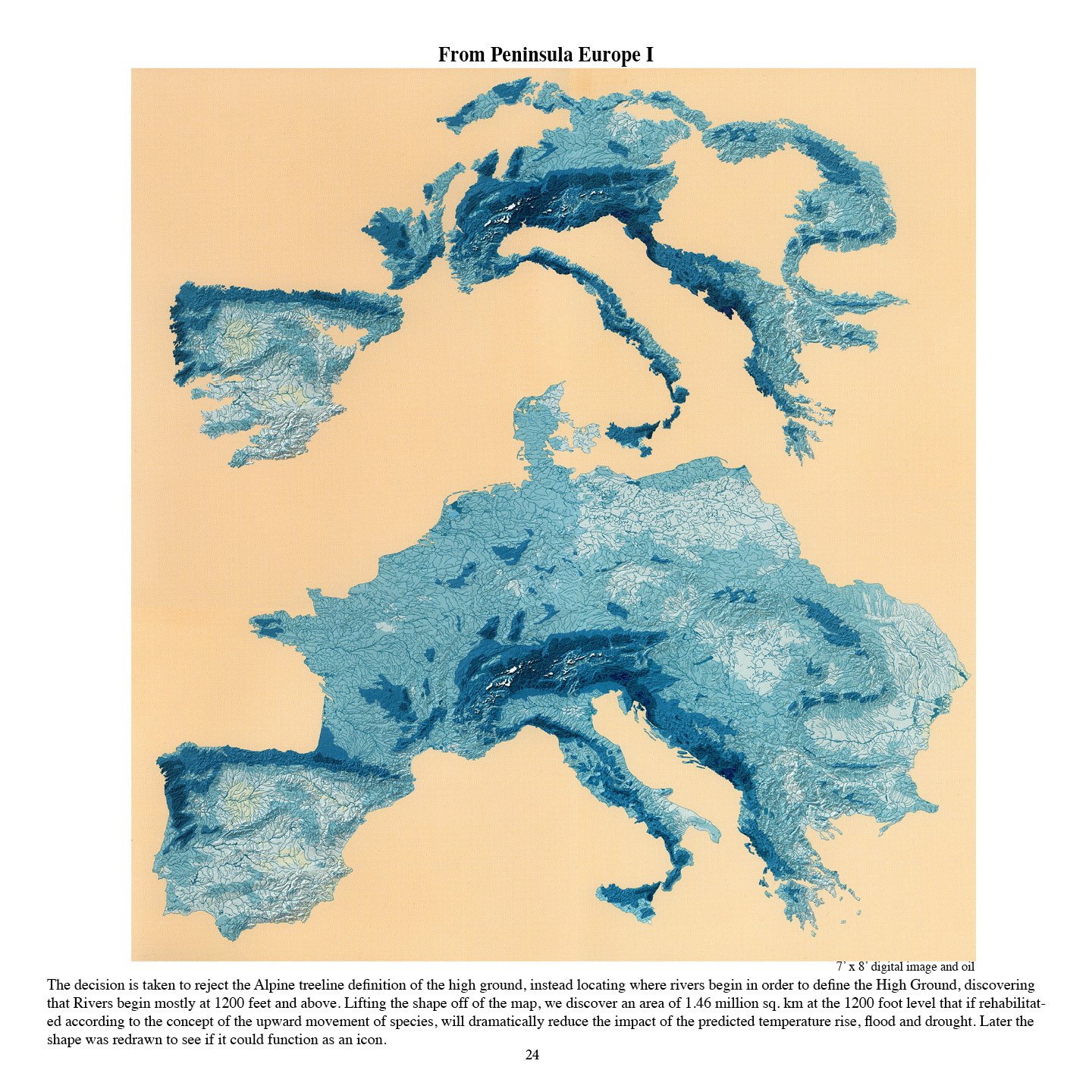

Another five years go by. We were busy with urban, bioregional and watershed works. In Bonn, Germany, working on the “Endangered Meadows of Europe” we again run into climate change. In the mid 1990’s our botanist friends told us the evidence was clear that species were moving, and even dying as Spring began happening earlier, and Autumn later. All this was in response to accelerating global warming. So we asked the question, “What would live in the city of Bonn, actually in the middle of Germany, actually in the middle of Europe, if the temperatures were rising and did so to the amount of 3 degrees?” All our science friends saw a 3 degree rise (some only a rise 2 degrees) as becoming very probable. They also saw the 3 degree rise as a tipping point after which everything changed. Some thought change might be barely manageable, others thought it would be catastrophic. All agreed the weather would become erratic, droughts would become normal, glaciers would melt and ocean waters would rise, food production would be reduced and parts of our civil society would be in danger of collapse. In response to this grim view of things that many people thought extreme and speculative at best, some few people, we among them, thought would become the new norm. We designed a work entitled “The Garden of Hot Winds and Warm Rains”. In it we assumed two greenhouses, each with a temperature rise of 3 degrees. The one with a wetter climate, the other a more desert like climate. With the Director of the Botanical Institute and Botanical Garden of the University of Bonn, Dr. Wilhelm Barthlott, we put together a team of his students, botanists and a paleo-botanist. The idea again began with questions. Could we, with our small group of “experts”, put together, as an act of collaboration with nature, two different botanical groupings. Each group would be adapted to temperature rise. One of them adapted to the wet climate and one to the dry. Finally, could these groupings be designed to be bio-diverse, useful to fauna of all kinds, yet harvestable in part by people. The point was that in this envisioning the harvesting was managed so that it preserved the system, thereby guaranteeing systems continuing with input balancing output and monocultural activity made impossible. The answer was “Maybe”, if the population was controlled, but to the question “would it be enough?” and what we meant by it, the answer continued to be “No”. Something was still very missing.

Another decade passes. It’s 2006 and we had just finished producing the work “Greenhouse Britain”. In it we made 5 proposals for the island, all in response to an accelerating global warming. We were reflecting on a very complex, large-scale installation, and again posing the question, “Would this be enough?” Even if these proposals were duplicated globally, place-by-place, and continent-by-continent, the answer still was what had now become a constant “No”. What if there was no “Yes” became a few days of thinking and depression.

It was 2007. In a morning conversation reviewing all these works over so many years we came to understand in a less than a 20-minute moment, that the great forces set into motion we had v=been talking about were seriously at work. In practice, entropy had been accelerated in most planetary ecosystems that we could understand. In fact, if there was indeed an arrow of entropy, Eco-systemically speaking, it is possible to imagine that, with great effort, ingenuity and creativity we had collectively gotten it pointed in the wrong direction. We had done this through our processes of “being civilized” which included population explosion, an energy use explosion, and runaway economic development, just to name a few. That which had been invisible to us was the outcome of a great force we, as creators, had brought into being.

All of this thinking and working lead to the formation of the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. It was 2009 at UCSC where we were teaching a graduate projects course that dealt with art-making with a global reach, underpinned by one or another forms of ecoliteracy. The Dean of the Arts Division, David Yager, announced rather boldly that anyone in the Division who wanted to create a Center could do so and would be supported if they could justify such a proposition. We asked him, “How about an Institute?” He said “Institutes are bureaucratically terrible to deal with at this University, where as a Center is a simple matter and has many of the qualities of an Institute, but few of it’s problems.” So with a lawyer friend we designed The Center for The Study of the Force Majeure with the idea that he would be the Director until we found a more effective Director. This finally turned out to be ourselves. The Dean approved, an advisory group was formed. Within 6 months the Metabolic Studio had granted our Sagehen research concept on assisting the migration of species $220,000 to proceed.

The Center, in its Statement of Purpose, defines the Force Majeure as the pressure of global warming on all planetary systems, in collaboration with the industrial processes whose negative effect on the environment has perhaps co-equally accelerated over the past 100 years. The Center believes that we must adapt ourselves to a very different world and that is the basis of our research.

For instance, the Center defines the type of problem it deals with as an ennobling problem. Ennobling refers to the effect of the feedback, which addressing the issues at this scale, has benefits to the individuals involved, as well as the human culture and the planetary environment as a whole.

In its present state the Center sees the activity of inventing ecologically-based, large-scale adaptation systems to the extreme change in the environment as necessary for our survival. Enhancing the sponge properties of soil in the Peninsula Europe work being one example.

Seen metaphorically, two frontiers are emergent and evolving exponentially. The one is a wavefront of water, advancing on all edges of all continents that touch all oceans. The second frontier is a heatwave increasing (apparently slowly but in fact exponentially) covering, touching, and effecting the whole planet and all lives in it. These two frontiers are different from all other frontiers that have been part of human experience. All other frontiers have been ones that we have advanced towards, often conquering or exploiting to our own advantage. However, these two new frontiers are ones that move toward us. Ones that where exploiting resources for production, consumption and profit, are not meaningful first approaches or behaviors. Rather, these two frontiers are such that we must adapt ourselves to meet them at the scale on which they are operating. The body of work that follows this rumination, Peninsula Europe, Tibet is the High Ground, Sierra Nevada pieces and the Bays of San Francisco, all seek to address what the Force Majeure means. All seek to address how one might cope with these circumstances. Finally, they are done as a response to the probability of extreme stress that the Force Majeure suggests is upon us.